Mobile Digital Computer Demonstrated in Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Video

Andrew Wood, a Deputy with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, was returning from a call to investigate a fire at Calabasas High School when an email came in on his Mobile Digital Computer. Wood began typing out his reply to the email, confirming that he had investigated the fire and was already returning from the call.

He never finished his response. As he later explained, a cyclist he did not see had suddenly, inexplicably swerved into his path on a curve in the road. Wood crashed into the cyclist, who was thrown up against the windshield, shattering the windshield and killing the cyclist on impact.

Wood’s explanation—that the cyclist had suddenly swerved into his path as Wood was passing the cyclist—is so common among careless drivers that it has its own acronym: SWSS, meaning “Single Witness Suicide Swerve.” When the driver involved in a car-on-bike crash is also the only witness, cyclists do some really inexplicable things, like “suddenly swerving into the driver’s path,” or “coming out of nowhere.” Sometimes, cyclists are even invisible, because, as happened in this case, the driver will later explain “I never saw the cyclist.”

Except there were witnesses this time, and according to the witnesses, the cyclist, Milt Olin, 65, had been riding in the bike lane, and never swerved into Wood’s path. Instead, Wood had missed the curve in the road and drifted into the bike lane, slamming into Olin from behind.

While he was typing an email on his computer.

There was more. An investigation revealed that Wood had been texting his wife, and had sent 6 text messages in the 4 minutes preceding the collision. Wood admitted to sending a text immediately before the collision, but stated that he had sent it while stopped at a red light. A later investigation by the attorneys representing Milt Olin’s family revealed that he had in fact sent the text while he was driving, shortly before he began typing his email response on his computer.

The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department began an investigation of the collision, and for many cyclists, the impartiality of the Department investigating one of their own was called into question. These suspicions were relieved, however, when the Sheriff’s Department recommended that criminal charges be filed against Deputy Wood.

The relief that justice would be served was soon laid to rest, however, when the District Attorney declined to prosecute Wood. The only avenue left for justice would be through a civil suit. And through that avenue, some measure of justice was achieved some four and a half years later, in 2018, when the County of Los Angeles settled with Milt Olin’s family for nearly $12 million.

There was one other victory for cyclists and other vulnerable users: in 2015, a little more than a year after Olin’s death, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department revised the rules for the use of Mobile Digital Computers. Under the new rules, Sheriff’s deputies may only type on the computer when they are pulled over or stopped at a light (with certain exceptions made for emergencies).

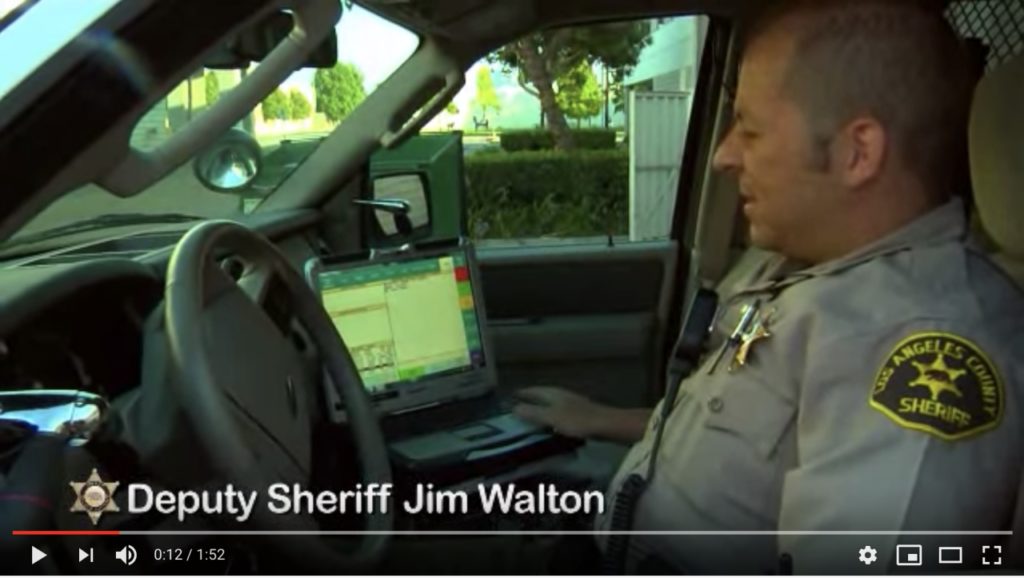

Watch: Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department video demonstrating the Mobile Digital Computer

This victory came as a result of the intense media focus on distracted driving by law enforcement officers. However, Milt Olin’s death was not an isolated aberration in a sea of good driving. To the contrary, distracted driving is epidemic on our roads.

In 2017, 3,166 people died as a result of all forms of distracted driving (including cell phone use, eating or drinking, talking to passengers, and adjusting the stereo, entertainment system, or navigation system), and 1.5 million car crashes were caused in the United States by use of a cell phone while driving. Between 2012 and 2018, 9% of all traffic fatalities were the result of texting while driving, and 14% of all distracted driving deaths were the result of cell phone use. In 2018, texting and cell phone crashes in the United States accounted for $129 billion in economic costs.

Related Article: Deadly Distractions, Part 1

And yet while taking your eyes off the road for “just” 5 seconds at 55 MPH is like driving the length of a football field while blindfolded, in a national survey 36% of drivers between the ages of 18 and 24 admitted that they have texted while driving, while 33% of drivers aged 18-64 have admitted to sending texts and emails while driving—and an astonishing 19% of all drivers admitted to surfing the internet while driving.

And while Milt Olin’s death generated intense media glare—as much for the fact that he was a prominent Los Angeles entertainment attorney as for the shocking circumstances of his death—there have been many other examples of texting drivers severely injuring or killing cyclists, including:

- On September 20, 2013, a cyclist was hit from behind near Koroit, Western Victoria, Australia. The cyclists suffered severe injuries, including a spinal fracture that doctors feared might leave him a paraplegic. The driver, Kimberley Davis, had used her phone to send and receive texts 44 times to 7 different phones before running the cyclist down, and was originally charged with 47 offenses, including 44 charges for each text message. She pleaded guilty to dangerous driving. It was revealed in court that when police contacted her two days after the collision to ask about her phone use, she said “I just don’t care because I’ve already been through a lot of bullshit and my car is like pretty expensive and now I have to fix it. I’m kind of pissed off that the cyclist has hit the side of my car. I don’t agree that people texting and driving could hit a cyclist. I wasn’t on my phone when I hit the cyclist.” Despite her perception that the cyclist had hit her, the police investigation concluded that “the cyclist was on the edge of the road heading west when Davis hit him from behind, despite there being lights on the back and front of his bike.” Davis was fined AU$4500 and had her license suspended for 9 months.

- On August 30, 2014, cyclist Peter Linden was hit from behind and killed near Rainier, Oregon. The driver, who had been texting on his phone at the time of the collision, was arrested by the Oregon State Police 5 miles from the crash scene, and was charged with first degree manslaughter, felony hit and run, and a misdemeanor out of Washington County for Fail to Appear. After pleading guilty to criminally negligent homicide and failing to perform the duties of a driver to injured persons (hit and run), Kristopher Lee Woodruff was sentenced to two years in prison, five years of probation, and had his driver’s license suspended for 8 years.

- On June 2, 2016, cyclist Eric Bell was run down while walking his bike in a crosswalk in Guam. He driver that struck Bell had run a red light, and it was later revealed that he had been texting while driving. The driver, Eddie Camacho, was charged with manslaughter, vehicular homicide, negligent homicide, reckless driving with injuries, disobey of a traffic signal, obstructed or reduced view: windshield, speeding, imprudent driving and failure to yield. Camacho subsequently pleaded guilty to one count of negligent homicide as a third-degree felony, and was sentenced to 1 year in prison, and a $1000 fine.

- On April 8, 2019, cyclist Douglas Sager was hit from behind and killed in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. The driver, who had been texting immediately prior to the crash, said she “never saw him,” despite having a 748 foot clear line of sight. The driver, Phyllis Emery, has been charged with homicide by vehicle, involuntary manslaughter and three summary offenses, including prohibiting text-based communications.

Here’s the problem we’re up against: Intentional distractions, such as texting while driving, or using a cell phone while driving (whether hand-held or hands-free) have the same impairing effects on drivers as does Driving Under the Influence of Intoxicants. And yet while we take intoxicated driving seriously, with serious penalties attached to DUI, we don’t take distracted driving seriously enough to do anything more serious than penalize distracted driving with token $20 fines…up until the moment a distracted texting driver kills somebody. Then we suddenly change gears and throw the book at the driver. It’s schizophrenic; texting while driving is “no big deal,” until wham, book thrown, it is a big deal.

We have completely discounted the deterrent effect that laws and enforcement have on behavior. Consider an analogy: Speeding is the number one factor in automobile crashes. And yet virtually every driver speeds. However, few drivers are willing to risk a speeding ticket with blatant disregard for the speed limit. We modify the behavior of drivers by placing limits on their speed, and enforcing those limits with costly citations. We modify the behavior of drivers by attaching serious penalties to DUI. People still break the law, but most are also cautious to avoid blatantly breaking the law. So we don’t just rely on hammering lawbreakers after they cause a deadly collision, we encourage them to not engage in dangerous behaviors in the first place, through fines and enforcement.

And that deterrent effect is where we’re failing when it comes to distracted driving.

Epilogue

Milt Olin was a prominent Los Angeles entertainment attorney. A former executive at Napster and A&M Records, Milt moved on from the C-Suite to co-found a law firm with David Altschul, a former executive at Warner Records. Together, they built a boutique law firm specializing in entertainment and intellectual property law, with a client roster that includes Michael Franti, Walter Afanasieff, Rick Dees, The Bicycle Music Company, Red Frog Events, IMVU.com, PlayNetwork, MetroPCS, SanDisk, Tom Petty, Fleetwood Mac, A&M/Octone Records, Pandora Radio, LyricFind, and the Estate of Bing Crosby.

Following his death, Olin’s family established the Milt Olin Foundation to advocate for the elimination of distracted driving related fatalities and injuries. Headed by Olin’s widow, Louise Olin, the Foundation has attracted the support of Olin’s law partner David Altschul, entertainment industry figures, and retired pro racer David Zabriskie.