Adventure Miles: Taming Nature

By Miles B. Cooper

In a fog

“Careful in the fog.” Parting words from the night manager as I rolled my rig out the front door. Careful indeed. An unseasonable marine layer had crept in from the ocean overnight, making the cool, dark morning cooler and darker. Five a.m. With a little luck and effort, I had enough time to get up and over the Santa Ynez Mountains’ first ridgeline, drop down to its namesake river, dirt explore, and climb back out for afternoon meetings.

This was my first opportunity to return to Santa Barbara since the virus changed the world. Work required I come down, so come down I did, Amtrak’s Coast Starlight serving as rolling office. Amtrak’s willingness to accept a bicycle fully assembled on the luggage car meant I was able to ride to the station, board, and ride away at the other end. Work also meant the Swiss Army bike, a battered old mountain bike that did not look out of place locked up outside, even if it did have a few sleeper upgrades.

Mission Santa Barbara in pre-dawn darkness.

Mission Santa Barbara in pre-dawn darkness.

I mounted up and spun the pedals. Up State Street, converted during the pandemic from a traffic sewer to an outdoor seating-laden pedestrian haven. A right on Mission, and up a little hill. The ascent angle asymptotically increased as I rolled from ocean flats through mountainous precursors. As I did, the gray damp transformed to black warmth, as if passing through a thermocline.

I rounded a turn and Mission Santa Barbara itself came into view. The mission’s symmetry and its architectural impact poses a dilemma when juxtaposed against the mission system’s troubling indigenous subjugation.

Mission accepted

Catholicism and its internal conflicts, in an indirect way, was my Santa Barbara trip’s genesis. A sisterhood, the Immaculate Heart of Mary, with deep Los Angeles social justice roots, had acquired a large parcel in Santa Barbara’s neighboring town of Montecito in the 1930s for the sisterhood’s novitiate training and spiritual retreat. Fast forward to the late 1960s, when a reactionary Los Angeles archbishop engaged the staid yet rooted sisters in an increasingly fraught pas-de-deux. Add the artistically gifted sister, Corita Kent, who drew increasing international attention for spiritual anti-war brilliance, and a patriarchy throwdown was all but guaranteed. When the dust settled, the sisters decamped the Church — property and intellectual property in tow — to start afresh as the spiritually warm yet iron-willed Immaculate Heart Community. If this thumbnail whets your appetite for more, check out the documentary Rebel Hearts. One of IHC’s missions continued to be the Montecito spiritual retreat center, known as La Casa de Maria.

Mine turnoff sign to Forest Route 5N18 along Gibraltar Road.

Mine turnoff sign to Forest Route 5N18 along Gibraltar Road.

In January 2018, following the utility-caused Thomas Fire that denuded the Santa Ynez Mountains above Montecito, heavy rains on the weakened mountainside brought the mountain down. In the early darkness, as the slurry accelerated down, massive boulders led the way, bouncing in and out of creek beds, mashing anything in their path. That included a high-pressure natural gas transmission line, buried under San Ysidro creek. Next came the mud and rock itself, sluicing across the alluvial plain. Gas-perfused mud ignited, along with a fireball that lit the night sky. When the rumbling stopped, 23 people were dead, countless injured, hundreds homeless, and a community permanently altered.

La Casa de Maria, adjacent to San Ysidro creek, was buried. Fast forward almost four years, and the utility company wanted access to the retreat center so its team of experts could pick apart the repair estimates. Hence my trip, as one of Immaculate Heart’s counsel, guiding them through another asymmetric conflict. But if they successfully stood up to a 2000-year-old patriarchy, what chance did a utility company have?

Pride cometh

Thinking about the Sisterhood’s strength under pressure got me well into the Gibraltar climb proper, the pre-dawn sky reddening. In the dark, partway up a blue-ribbon climb, no-one else around, I momentarily felt a little too impressed with myself. A solitary headlight caught up to me, another cyclist passing as if I were in slow motion. She uttered a clipped hello before she was out of sight. Some who strive find tension between challenge and pride. The fates tend to help by serving up a healthy dollop of humility whenever pride takes the lead.

The access road to the Sunbird Quicksilver Mine apparently used to be passable.

The access road to the Sunbird Quicksilver Mine apparently used to be passable.

I watched the rider’s flashing red taillight disappear and reappear around turns higher and higher as she bounded up the mountainside. Gibraltar’s a long, exposed climb. It was not my first time up, however. That had been a couple years prior as I explored the Thomas Fire’s burn scar and the watershed. On that journey I encountered snow patches, unusual for the area. But what was usual weather now? Historic droughts followed by historic rains. As humans attempt to mold the earth to their purposes, we increasingly unbalance matters. Nature’s responsive oscillations will eventually rebalance the planet. We humans just might not be around to see it. Humility served as Last Rites.

Dark thoughts were difficult to maintain as dawn’s light turned the monochromatic landscape into technicolor brilliance. The pedals spun. The summit came into view. I was thankful to have full light for the next evolution. As Gibraltar Road crossed East Camino Cielo, it became a gated fire road and a ripping descent into the Santa Ynez River basin. It was here that the slow-climbing Warthog, my wide-tired, flat-barred old school rigid mountain bike, shone. Elevation gains eked out pedal stroke after pedal stroke disappeared in minutes, a mile-wide grin pasted across my face. As I got lower and closer to Gibraltar Dam, I kept a lookout for an old wooden sign, along with a road and gate to the right. This turnoff led to the abandoned Sunbird Quicksilver Mine, a five-mile out-and-back foray.

Extraction industry

Whether it is called cinnabar, quicksilver, or mercury, the rendered element serves a purpose. That purpose was significant in gold extraction, as mercury combines into an amalgam with small pieces of gold in sediment and soil, making it easier to gather. The mercury is then vaporized. As the California Gold Rush boomed, so did related industries (just ask Levi Strauss). Gold mining begat mercury demand, and thus meta extraction’s quicksilver mines. Sunbird Quicksilver Mine opened in the 1860s, when a prospector determined the red rock likely contained quicksilver. The red ore was crushed and heated in furnaces, with pure mercury being condensed off. Healthy work for the upward of 400 people who worked the mine at its peak.

Remaining mine buildings and Warthog.

Remaining mine buildings and Warthog.

The mine ceased operations a long time ago but remained a permitted mining inholding within Los Padres National Forest until the mine owners failed to renew their permit in 1991. Now, the abandoned site sits fenced off, above Gibraltar Dam, near the end of a forest service access road. Or at least it is called a road by the forest service. Judging by its condition, nothing beyond hikers and ambitious bicyclists have used it lately. The out-and-back included the roughest conditions on the ride and a surprisingly punishing descent and climb. For those interested in decaying industrial infrastructure, the trip does not disappoint, however.

It seems curious that a mercury mine and tailings would be left in this state near the shore of a municipal water system dam, but commissioned studies seem to find it perfectly safe. No one in Santa Barbara seems to be suffering from mercury poisoning, anyway. After poking around and a quick snack, I mounted up and headed back toward the dam itself.

Water and power

California’s coastline provides spectacular living, with a catch. Water is scarce. Santa Barbara approached this issue in part by damming the Santa Ynez River. Gibraltar Dam provides both water and hydroelectric power, but the dam is silting up. Not surprising given the savagely steep and sandy mountains lashed by strong winter rains. These rains seem increasingly less predictable, leading to extreme drought conditions on one hand and deluges like the one triggering January 9, 2018’s debris flow on the other.

There was no rain in sight on this 85-degree day. The dirt road rose to meet me, throwing rollers instead of lazing along the Santa Ynez River itself. Not being an engineer, I presumed the distance from the river protected the road from being inundated during winter storms. After a time, the dirt ended at a gate and Red Rock trailhead parking area. Thence began a rollicking paved descent, paralleling the Santa Ynez River. Just before the Rancho Oso RV Park was a sharp left, back onto the dirt, on Forest Route 5N20. Here began the final big push to get back up and over the ridgeline separating the river valley from the coast. Whether it was the grade, the heat, or the miles already ridden, I found myself walking sections.

Gibraltar Dam stores drinking water and generates power.

Gibraltar Dam stores drinking water and generates power.

Turning right, I got back on pavement, rolling along East Camino Cielo until it reached Painted Cave Road, where I made a left. Time to descend. As I did, I passed the road’s namesake, the cave’s entry barred off to keep people from adding their own artistic interpretations to the ancient Native American pieces. Called Alaxuluxen by the Barbareño Chumash, the cave can be explored virtually.

The twisting descent finally brought me to the flatter oceanfront plains of Santa Barbara, where I worked my way, primarily along Modoc Road, back to the hotel. The final section was uneventful, and I was beat. As I rolled along the last few miles, once again surrounded by cars and houses, I thought about our impact on our environment. Extreme weather events were now becoming commonplace. Our extraction industries have led many to tremendous wealth and comfort, yet we now may be at a tipping point where that comfort will end.

Epictetus, the Greek Stoic philosopher, taught us that if we seek to control the uncontrollable, we consign ourselves to misery. Can we control the climate? No. But we can influence it if we control ourselves. I can control myself, but I cannot control my neighbor. Through one’s efforts though, one can influence those around us. We should strive for small footprints with large impacts. Taking inspiration from organizations like Immaculate Heart, we can see how a few iron-willed people can turn the tide. With enough interlinking efforts, we have the capacity to effect change. Will it be enough to alter our direction? Perhaps. Perhaps not. But the challenge itself is worth the undertaking.

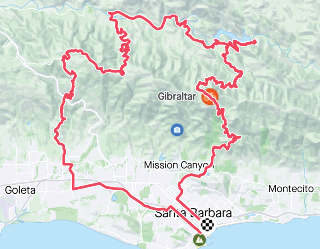

Considering the route?

About the author: Read more of Miles B. Cooper’s articles about bikes.

Have you or someone you know been involved in a bicycle crash? Want to know about your rights? Are you a lawyer handling a bicycle crash who wants the best result for your client? Contact Bicycle Law at (866) 835-6529 or info@bicyclelaw.com.

Bicycle Law’s lawyers practice law through Coopers LLP, which has lawyers licensed in California, Oregon, and Washington state, and can affiliate with local counsel on bicycle cases across the country to make sure cyclists benefit from cycling-focused lawyers.