From the beginning, the Bike Law Network has had a singular focus—helping cyclists who have been injured find justice. Well, what’s so special about that? Lots of lawyers take bicycle accident cases. But the Bike Law Network is different—the lawyers in the network are cyclists themselves, and they’re passionately committed to protecting the rights of cyclists.

Just how different is the Bike Law Network? Consider that one of the founding lawyers of the Network is Bob Mionske. Two-time Olympian. Professional racer. Bike Lawyer. Author of Bicycling & the Law. I recently sat down with Bob to talk bicycle law.

Rick: Hi Bob, thanks for taking the time to talk with me. You’ve got a resume that’s unique in the world of law: Two-time Olympian. Professional racer. Bike lawyer. Author of Bicycling & the Law. How did it all begin? Before Bicycle Law, before the Olympics, before the racing scene—you’re originally from Madison, Wisconsin, right?

Bob Mionske: Actually, I was originally from Evanston, just north of Chicago. My family moved to Wisconsin when I was a kid. That was where I first started riding a bike, although not for competition. The summer when I was 17, I worked for my dad in California, and saved up enough money to buy a new touring bike. That bike was my ticket to exploring Wisconsin’s forests and lakes.

Rick: Sounds like the life of Riley…

Bob Mionske: Yes, it was a surprising and completely new experience. That was the first time I had spent so much time in the saddle, riding the backroads, enjoying the exercise and getting stronger and learning a new sport. Cruising 100 miles in a day on farm roads was unbelievable that first spring!

Rick: Was that when you were at Madison?

Bob Mionske: When I was in high school in Wilmot, actually. After I graduated from Wilmot High, I enrolled at UW-Madison, where I was on the UW Alpine team and was dead serious about getting better. With limited funds and being a poor college student, I had to make do with so-called dryland training, so I continued to ride for conditioning. My second road bike was purchased in 1982 in Portland, Oregon after a summer of working at Timberline Lodge on Mt. Hood, waiting, making beds and cleaning toilets for the hotel and then summer skiing on the Palmer Glacier.

Rick: So how’d you transition from ski racing to bike racing?

Bob Mionske: It was through a guy in my Latin class. I noticed that he had shaved legs and thought he might be a bike racer.

Rick: When was this?

Bob Mionske: 1983

Rick: Right after Breaking Away came out?

Bob Mionske: [Laughs] Well, that was a few years before.

Rick: Bike Law founder Peter Wilborn says that he “was a Breaking Away kid.” What about you—were you like Dave?

Bob Mionske: [Laughs] No, that was Peter, I was more like Moocher. Actually, I was clueless about bike racing altogether. I was a ski racer, and riding to build my fitness for racing. Never saw a road racer until I got to college and still knew nothing about the sport, but I suspected that my classmate might be a bike racer, so I struck up a conversation with him. Turned out I was right, he was an amateur bike racer named Colin O’Brien. He worked in town for Andy Muzi at Yellow Jersey. So we talked bike racing, and Colin gave me some advice about bicycles and racing. In 1981, he set the national hour record, and later went on to join the national team.

I was already riding for fitness training, so after talking with Colin, I started racing bikes too.

Rick: So you made the leap from ski racing to bike racing?

Bob Mionske: Not at first. I was still ski racing, but I began racing bikes too. It was all part of my dryland training for ski racing. After a while, though, I was having better results racing bikes, so that’s when I made the leap. I began racing for amateur teams in 1986, and by 1987 I was racing for Andy Muzi’s Yellow Jersey team.

Rick: What was the race scene like back then? Where did you race?

Bob Mionske: I was on several club teams in the Midwest. I did a short stint on a team called Wood Spoke with Specialized Creative Designer Rob Egger, and we have been friends ever since.

When I was racing in the US, it was decent prize money. If you could get into the top three, you could literally pay for your living. But if you got a flat, or you finished out of the top ten, which in bike racing happens a lot, you didn’t get paid at all, and if you finished out of the top twenty, then you were out the entry fee, the gas money, couch surf, and all your food. Bandages. It was rough, but it was still better than it is now.

So I basically existed for those first three years on what would euphemistically be called the “crit circuit” around the MidWest, which was really pretty vibrant considering the state of American bike racing back in the ‘80s. I had weekends where I made $3,000; you can’t even do that now, 35 years later, unless you’re at a really big race. And if you’re at a really big race, you’re going to be competing against well-supported professional teams. But back in those days, there were big criteriums in Chicago, Minneapolis, Milwaukee, Cleveland and Cincinnati, St. Louis, Madison, and you’d go from weekend to weekend.

And the same with “primes,” money that they pay on a lap. They ring a bell and they’ll pay money when you come around next time. Sometimes you could do that. I remember a race I was at in San Diego, where I was living on potatoes, couch surfing, and even sleeping outdoors with my friend in his beat-up BMW, and it was a loose-cash prime, where they walk around, the announcer gets the fans whipped up, and everybody throws money into a hat. And it can come out to be a lot of money. In this case, I didn’t know what it would be, I think they were saying it was close to $500, which was huge. And I decided there’s no saying what could happen between now and the finish of the race, so I decided to go for it, and I ended up going against this famous English sprinter named Russell Williams, and I got second. So everything for nothing, and I left everything on the road, and he won it. He was a real colorful racer from England that was coming over here and just killing us.

So that’s how it was, couch surfing, borrowing money, patching our own tubes on the sew-up tires. You’d have to open them up, take the thread apart, pull the tube out, and then fix them like you would any other inner tube, then stuff it back in, and then sew the sew-up back, and then glue the tape back on, and then glue the whole thing back to your rim, because we raced on sew-ups, which were glued to the rim. Which they still do at the highest level, although I guess they’re pretty much going to tubeless now, I’m not really sure if they’re using clinchers at that level. But back then, we did it all ourselves.

But when I first got a Fed Trip (which simply meant you were on a US Cycling Federation team trip abroad) to Europe, I was always supported by the US team. When I went over there in 1986, on one of my first trips, to race in Italy, we were an oddity. People would gather around our team just to see Americans that were actually there to race bikes. It was really strange for them, maybe like a Russian baseball team over here, just an oddity. And it was harsh.

We didn’t know the roads, it was different food, a different time zone, we didn’t have the best vehicles for racing. The U.S. team did a pretty good job of supporting us, but when you were on some of the smaller Federation trips in the early days, it was really cobbled together. We would find somebody that would put us up, we didn’t stay in hotels, typically, for most of the races for the duration, until we were on the race. In between races, we just had to get by, but again, the Federation supported us. There were no cell phones, and it was difficult to call internationally, a lot of times you couldn’t get through. The currency was different in every country, there was no European Union. And so you could really go to Europe and get lost. And with the language, racing in some countries, no one spoke English, and it was really helpful to have a local that that would take you under their wings, but we didn’t always have that.

So that was kind of the European experience, and unfortunately, most of the racing was in their winter and spring, which is very cold and wet. And those are not the kind of conditions you want to compete in when you don’t have great fitness, because you won’t be able to stay in contact with the field. You’ll be spit out the back and riding on your own in 42 degrees and pouring rain, which happened to me in Germany. One of the more brutal experiences I’ve ever had. We mostly we got our asses handed to us, although there were exceptions to this. But the exceptions were so few and far between as to make them notable.

This slowly changed and a new generation of riders began to emerge due in large part to the experience and support of those who had gone over the pond in earlier years. Of course, Greg Lemond was a superstar already, and there were some really talented Americans, but we amateurs were mostly just getting thrashed at the biggest races.

Rick: I think that for those of us who’ve never raced, it’s a real eye-opener to think about the sheer guts and grit and determination to succeed that it took to overcome the hardships of racing—not just the races themselves, which are obviously pretty grueling, but all of the other hardships you have to endure just to get to the next race. And that determination paid off, eventually, when you earned a spot on the U.S. National Team for the 1988 Olympics. You came very close to winning the bronze for the men’s road race that year. It was a very close race, wasn’t it?

Bob Mionske: It was a fast race without a big hill so, of course, the race was very intense. I was on a three-man team and we were all about the same level at that time but I made the right move and was able to get in a break away on the last lap. Two riders, Olaf Ludwig (an East German) and Bernd Gröne (a West German), took off. I stayed back on our group hoping we would chase, but instead I was sprinting for 3rd now. In this remaining group was Djamolidine Abdoujaparov (“The Tashkent Terror”), one of the world’s fastest sprinters. I was able to overtake Abdou but Christian Henn beat us both for the bronze and I finished 4th. Ludwig, Henn and Abdou would all eventually test positive in their careers. Bernd Gröne ended up quitting over his refusal to dope, to his great credit. This was during the dark years of road cycling, and it was far from a fair playing field.

Rick: From what I’ve read, it was even more dramatic than that. The race for 3rd came down to a photo finish, and Henn won by a tire’s width. There’s a photo out there of you throwing your bike across the finish line—is that from that race for bronze?

Bob Mionske: Ya, that’s the one. In a finish that close, as you’re sprinting for the line, you have to throw your bike across the line, hoping that will get you across first.

Rick: People only talk about the podium, and I know you don’t like to toot your own horn, but that 4th place finish was kind of a big deal. In fact, it was the best result by an American cyclist at a “full participation” Olympics since 1912, and as a result of that race, you received the USCF (now USA Cycling) Amateur Cyclist of the Year award. What was it about a “full participation”Olympics that made it so significant?

Bob Mionske: The Eastern Bloc weren’t allowed to turn professional. So you had the countries of Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Poland, the Soviet Union, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and all those countries, the Ural mountains, it was all part of the Soviet Union then. If you look now at those countries, whether they’re Russia or independent now, and you see their representation in the pro peloton now, you see that bicycle racing is quite popular and they’re quite good at it. Well, these guys weren’t at the Olympics in 1984. Because Carter boycotted Moscow [in 1980]—because of Afghanistan, ironically—they boycotted us in L.A. [in 1984]. So the American team had four guys in the top ten, they were very good riders, but they weren’t really going up against the same athletes that they would have if the Olympics had been fully attended.

At that time, the Eastern bloc countries were dominant in cycling, because they took the sport seriously, and also because they had doping programs. As it turned out, it’s no longer a secret that the Soviet Bloc, and even the Russians to this day are obviously having serious problems with state-sponsored cheating. And back then, it was an ideological cold war, so athletics was a proxy war, and a place to see whose system was producing the best athletes. So they held nothing back. They had incredible raw talent, they had the state apparatus behind their athletes, whereas we were kind of a voluntary sport that was kind of under the radar in the United States at that time.

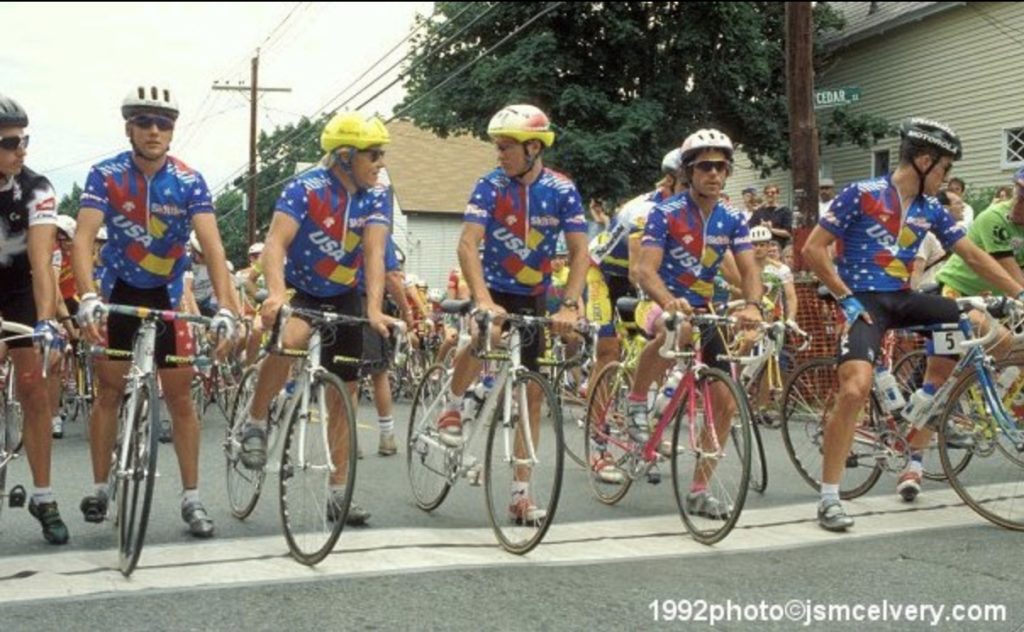

Rick: Things started happening pretty fast for you after that—you were the 1990 National Road Race Champion and rode for the United States World Championship Team in the UCI Amateur Road World Championships in Japan. In 1991, you rode for the United States Pan-American Championship Team, placing 6th in the Men’s Individual Road Race in Havana. And then in 1992, you made it onto the U.S. Olympic Team for a second time, but the results were very different from the ’88 Olympics.

Bob Mionske: In ’92 I got food poisoning, salmonella poisoning, three days before the race. Coach Chris Carmichael got it too. We were the only ones who ate the second helping of garlic aioli, and it was spoiled, and I got really, really sick. I offered my spot to George Hincapie, but Chris said, “no, you’re the guy,” and I stayed in bed a whole day, and tried to hydrate. And I felt pretty good, actually, in the race. The plan was that I would get in the early break away, which I did, and I was feeling fantastic, and in fact my break away companions got first, second, and third. But I faded, dropped out. Lance tried to bridge across, he was actually in a perfect place, but he just didn’t have the legs. He was actually at his only down point in the whole season. Unfortunately, it was during the Barcelona road games. So it was a disaster for both of us.

Rick: That’s such an incredible story, coming so close to another race for the podium, only to be dropped by the garlic aioli. And yet, all joking aside, you somehow pulled really deep to come back from food poisoning. It’s another behind-the-scenes tale of the sheer will to endure through hardships that most people will never know. So after that race, was that when you turned pro?

Bob Mionske: Ya, in ’93 I was riding for Saturn. They were an amateur team, but they made the move from amateur to pro that year, so now I was riding on a pro team.

Rick: Who were some of the guys you were riding with then?

Bob Mionske: In ’93 the Saturn team had Kevin Livingston, who ended up being on the U.S. Postal Service team with Lance Armstrong, being his famous first lieutenant. We had Brian Walton, who’s an Olympic medalist from Canada. There were three or four Olympians. The team was basically track and roadies from the U.S. National team, so we had a lot of good guys.

Rick: ‘93 was towards the end of your racing career, right?

Bob Mionske: Ya, after the ’93 season I retired from racing, but I spent the ’94 season as the Team Director for Saturn, before retiring from racing.

Rick: So after you retired from racing, you moved to Oregon and enrolled in law school. That’s quite a transition, from pro racing to law school. What led to your decision to study law?

Bob Mionske: I knew I couldn’t make a living racing bikes any more, and after one year of coaching and being a director, I was tired of the road and I needed a career. So I bought a coffee shop and worked that for a year and a half. And at the time, I had a bunch of friends that were lawyers, and some of them suggested that I go to law school. Additionally, my wife at the time wanted to go to law school, so we both signed up together.

Rick: After you graduated, you opened the first law practice in the country—probably in the world—whose clients were exclusively cyclists. Around the same time, you began writing a legal advice column for cyclists—still going strong all these years later—and you coined the term “bicycle law” to describe your practice. At the time, you were a pioneer in a world where other lawyers were focusing on “slip and fall” and auto accident cases. Now bicycle law is a crowded field. Can you tell me how you came up with the idea, what it was like then, and what changes you’ve seen over the years?

Bob Mionske: By the time I got to the end of law school, I realized that the standard legal occupation wasn’t going to be a great fit. I had thought that I wanted to be a trial attorney, which I thought was the closest thing to competing at a high level in sports, but that didn’t really turn out to be the case, in my experience. So I started looking at different niches of law.

I had been called to be an expert witness at a bike injury case, and I thought maybe I could specialize in bike injury work, even though there weren’t going to be that many collisions, because biking wasn’t all that popular yet. I thought maybe I could do it in a couple of different states, so I got licensed in a couple of different states in the early years and tried to make a go of it. And I got my first case, which was a dooring case on the campus of the University of Wisconsin. It was slow at first, but then it started to roll.

And at that point I made the decision to move back to Oregon, at about the time that cycling just exploded. The Lance Armstrong phenomenon came along, and all of a sudden everybody and their brother was riding bikes to work and getting road bikes and the sport seemed to get thrust into the limelight, in large part because of Lance Armstrong, but also because cities were getting more and more congested and people were looking for more ecological, healthy ways to transport themselves. So there was a bit of kismet there, and like any kind of strike of lightning, when you find something good like that it’s not long before it catches on, and it really did catch on. But to begin with, I had to come up with something to call this niche, and so I called it bike law, and I called myself a bicycle attorney.

And it turns out Peter Wilborn was doing the same thing for much different reasons at about the same time—actually, tragic reasons. And we both went about having our own practices, and eventually started bumping into each other, and realized that it would be better to work together to represent cyclists. Especially when it comes to advocacy and establishing our rights to the road in the national platform, so that was really essentially the launch of the Bike Law Network. Peter had something started, and he asked me to join.

Rick: So, I wanted to run through a synopsis of your law career while all that was happening: In 2002 you came up with another novel idea—you began writing Legally Speaking with Bob Mionske, a bicycle law column in VeloNews. Originally it was kind of a standard legal column for cyclists, but around 2005 or so, when I started working with you, you began to transition to cycling advocacy in your articles.

I was still in law school then, so answering questions about legal issues was standard training for law. But when you started moving into advocacy, I was fully on board with that. We were doing some work that I think we both felt was vital, trying to bring the injustices against cyclists out into the open, asking why these often horrendous injustices were “OK,” trying to bring about some changes to make the roads safer for everybody, really, but especially for vulnerable users like cyclists. Every now and then I would hear from some of the people we helped, and it was extremely gratifying to know that we were able to make a difference in people’s lives.

Then, in 2007 you made another transition, and we went from writing a legal column about bicycle law to writing a book about bicycle law. That book—Bicycling & the Law—was interesting, for a number of reasons. For one thing, it was kind of a hybrid of bicycle law, practical advice for cyclists, and advocacy. In particular, you advanced the legal argument that our right to the road is a constitutional right. I remember that you were very specific about wanting to make that argument, so I dug deep into old case law, and we were able to establish that cyclists do have a constitutional right to the road.

We also had years of very old case law and statutory law establishing that cyclists had a right to the road. And while we were researching where these rights came from, we discovered some interesting things—for example, the first reported automobile crash resulting in an injury was in 1896, between a driver who lost control of his vehicle and a cyclist. Another thing we discovered was that we were writing the second book for cyclists about bicycle law; the first book, The Road Rights and Liabilities of Wheelmen, had been written in 1895.

Then, a couple of years after Bicycling & the Law came out, you began writing a column called Road Rights for Bicycling magazine. And now you’re back at VeloNews, writing your Legally Speaking column again. That is nearly two decades of writing and advocacy about the issues cyclists face, and about their legal rights. It’s an incredible body of work. But day to day, your law practice is focused on helping cyclists who have been injured in bicycle crashes. Do you see a connection between the issues you write about and the cyclists you help?

Bob Mionske: I do. You’re talking about macro level—the big picture—and micro level—the close-up. On the macro level, I talk about these big issues that affect all of us—our right to the road, careless and aggressive drivers, the enforcement of “imaginary laws,” the failure to enforce real laws, advocating against bad laws, and for better laws—all of these big issues and sometimes jaw-dropping injustices that make the road less safe for all of us. At the micro level, in my day-to-day law practice I work to help cyclists who have been injured by careless drivers find justice. We can’t go back and undo the collision, but what I can do is make sure that the driver’s insurance company compensates the cyclist for all of their injuries—their physical injuries, their rehab, medical bills, lost wages, damaged bicycle, and so on. And that is where these big issues we are talking about in my column become personal, specific issues that may have an immediate impact on my client’s ability to obtain justice. Often, if there is any way for the insurance company to reduce or completely deny compensation to the injured cyclist, they will.

So when I write about these issues, I’m trying to raise awareness at the societal level so we can begin to reverse these injustices, make the roads safer for all of us, and prevent as many injures as possible. And when I handle a case, I’m trying to make sure that these issues don’t interfere with my client’s ability to obtain justice.

Rick: In a related vein, what changes do you see ahead, for cyclists, and for the field of bicycle law? What are the opportunities, and what are the challenges? And where do you see all of this going?

Bob Mionske: One of the things is in the early years, it was really a matter of establishing our right to the road, and now it’s a matter of maintaining that. And we’ve made a lot of gains. We’ve really come a long way, to the credit of everybody involved. But one of the problems that is right at the sharp point of all of this, is that at the same time that we started to get acknowledgement from the government and from the society as a whole that we have a right to be on the road, it hasn’t lessened the antipathy and the problems. But at least motorists know we have a right to be there, and they can’t just hit us and keep rolling down the road, because it’s a hit and run. And everyone realizes that if a motorist cuts you off or violates your right of way, that they’re going to be responsible for your damages.

So that’s all been to the better, but what hasn’t been for the better is two things. One, familiarity breeds contempt. So now a lot of people are riding bikes in cities, and the older drivers, the baby boomer generation, that was a tough transition for them. But younger people, they see people on bikes growing up. Their school teachers, the adults in society, their parents, their neighbors ride bikes, so it’s not as novel, it’s not as unusual. But the other thing is that this obsession with holding devices and distracted driving, unfortunately, has increased year by year, and the younger drivers, the younger people who are becoming the majority of the population in the United States, cannot be without their devices in constant contact, and this is causing a huge problem, and there seems to be no answer as to what the solution is. We have vulnerable user laws, but unless there’s a technological change, people will still think it won’t happen to them, and they’ll take their eyes off the road. During the course of this interview, somebody’s probably been hit and killed, because people operating motor vehicles are failing to keep a safe lookout, because they’re distracted.

So things have improved, we’re mainstream, we’ve got pretty decent advocacy, although it’s two steps up, one step back, but then this distracted driving element has come from the side and become a brand new challenge for all of society. So that is the challenge.

Rick: That’s an interesting perspective. As you were saying that, I was thinking “we can just increase the penalties for distracted driving.” And we probably should. But even if we do that, it’s like you said, people will still think it won’t happen to them. There’s a psychological phenomenon called “Optimism Bias” where people think that because nothing bad happened the hundreds of other times they did something dangerous, nothing bad will happen this time either. And of course that’s a fallacy, but it’s extremely difficult to break through that kind of cognitive bias. So the real solution is probably going to have to be technological, as you said, but there are some major challenges to doing that. I know when I’m riding shotgun, I’m often on navigation duty, which means I need her phone even though she’s driving. I have no idea how to prevent someone from using their phone in the car, whether they’re driving, or a passenger, without affecting the ability of the passenger to navigate, make phone calls, etc. But ultimately, a technological solution is really the only surefire way to get drivers to focus on driving. I hope someone can figure out how to do it.

The other problem with distracted driving is when we do try to address it in the law, we focus on getting drivers to go “hands-free,” but the research shows that drivers are impaired even if their device is hands-free, and the level of impairment with distracted driving is worse than DUI.

Bob Mionske: It’s definitely a problem, one that we really haven’t got a handle on yet, and one that we still haven’t figured out how to get a handle on.

Rick: Bob, bringing it all back to where it began, you’ve gone from riding on a team to sponsoring a team.

Bob Mionske: Ya, I like to support racers, I still ride a lot, and it’s fun to be around the sport, and there’s a whole younger generation of racers that are getting experience in the sport now. Giving a little bit back to them helps them have a chance to race and compete, and so the Bike Law Network does a lot of things for cycling. There’s quite a bit of support for cyclocross, especially in Michigan, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Georgia, Colorado, but in Oregon I sponsor a traditional road team. We also sponsor what we call “Bike Law Ambassadors” all around the country. These are representatives of our organization. You’ll see them in Wattie Ink Bike Law kits all around the states.

Rick: That’s great to see. It really connects the Bike Law Network with cyclists in a way that celebrates the life-affirming sport we love, and I’m sure it really makes a difference for the younger riders coming up. Final question: Three things you enjoy that have nothing to do with cycling or law…

Bob Mionske: Let’s see… a Murakami book, a stand-up paddling session on the river, and my fur family. Those are three things that keep me sane.

Rick: And skateboarding?

Bob Mionske: That’s four things…

Rick: You got me there. Bob, that’s an extraordinary story of two very different careers, somehow woven into a cohesive whole that’s greater than the sum of its parts. I know every time we talk, you really have your finger on the pulse of what’s happening, and also an uncanny knack for anticipating the next big wave. Thanks again for taking the time to talk with me, and I think it’s safe to say we all look forward to your incisive takes on cycling advocacy for years to come.

***

Bob Mionske is a nationally-known bicycle accident lawyer based in Portland, Oregon, and affiliated with the Bike Law network. A former U.S. Olympic and pro cyclist, and a prolific advocate for the rights of cyclists, Mionske authored Bicycling & the Law in 2007, and has continued his advocacy on behalf of the rights of cyclists with his Legally Speaking column in VeloNews.

***

This interview, Bob Mionske: OG Bike Lawyer, Olympian, and More, was originally published on the blog at Bike Law on April 16, 2019.