Hananja Konijn was riding his bike home from school when he was right-hooked by a truck. He was knocked off his bike and dragged a few feet before the truck came to a stop. The next morning, Hananja, 12, succumbed to his injuries.

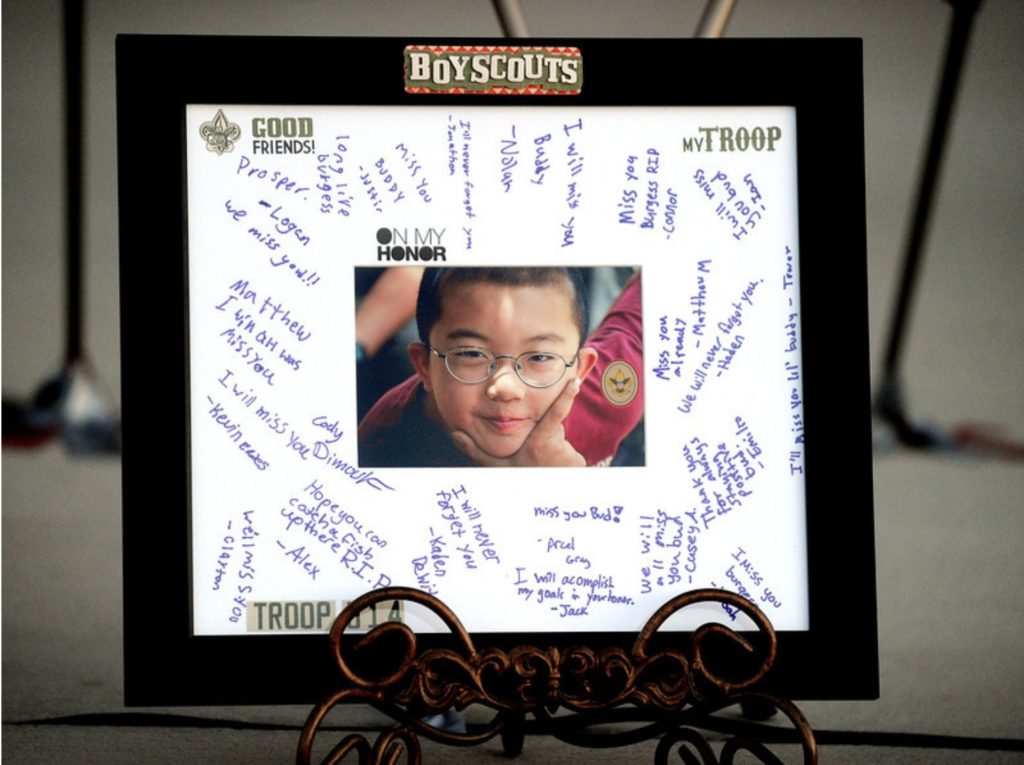

If Hananja had been killed in an American city, it’s likely that police would have decided that he was to blame. That’s what happened when Burgess Hu was hit by a car while riding his bike to school. Of course, because like Hananja, Burgess was only 12, the police went easy on him, only implying that the collision was his fault, rather than outright blaming him for his own death. Still, by implying that Burgess was to blame, while ignoring all evidence to the contrary, and bending over backwards to exonerate the driver who had made a right turn without looking to the right, the police made it clear where their sympathies lay.

Burgess Hu

Had the driver hit an adult cyclist in an American city, police and the media would have reminded all cyclists to obey the law, and to wear helmets, while ignoring the fact that the driver turned right while looking left. The public comments section of the news stories would have been far less muted, and far more venomous in their hatred of all cyclists. In some cities, police would have launched an all-out enforcement blitz against “scofflaw cyclists,” while ignoring the careless and reckless drivers and blatant law-breaking of the far more deadly scofflaw drivers.

Burgess Hu was spared the more extreme anti-cyclist hatred because he was a child, but he was still blamed by law enforcement for his own death, while the utter failure of the adults around him to provide safe routes to school, and to simply follow basic traffic laws and common sense while driving were completely and conveniently overlooked.

Had Hananja Konijn been killed in an American city, the response to his death would have been similar. But Hananja wasn’t killed in an American city. He was killed in Zoetermeer, in the Netherlands, and as would be expected in a nation that prioritizes protecting its cyclists, the response was markedly different from the response we would have seen here.

In the Netherlands, the law requires a police investigation when a cyclist is killed. So when Hananja was killed, police closed the intersection and went to work. This wasn’t an American-style investigation, where the police see a dead cyclist and decide the cyclist was at fault, no further investigation necessary, no charges necessary. When the Dutch police began their investigation of the collision that killed young Hananja,

“Along with clipboards and cameras and measuring tape, they brought with them an 18-wheeler and a child-sized bicycle. Over and over, they maneuvered the two around the corner, recreating the all-too-common “right hook” accident in slow motion, each time adjusting the truck’s mirrors or the angle at which it struck the bike.”

Under Dutch law, there’s a rebuttable presumption that the driver is at fault in a collision with a cyclist. This means that unless the driver provides proof that the cyclist was at fault, the law will presume that the driver was at fault. If the driver swears that the cyclist “came out of nowhere,” and the dead cyclist is unable to tell their side of what happened, the driver is still at fault under Dutch law. If the police refuse to do their jobs and conduct a proper investigation, the driver is still at fault. If a forensic investigation determines that the cyclist was at fault, the driver can rebut the presumption that he caused the collision.

This may seem unfair to American drivers, but it removes the unfair advantage that the still-living driver has over the now-deceased cyclist who can no longer tell their side of what happened. And it also provides an extremely powerful incentive for Dutch drivers to drive responsibly. “I didn’t see the cyclist,” “the cyclist came out of nowhere,” and “the cyclist swerved in front of me as I was passing,” all become useless as get-out of-jail-free cards in the Netherlands. Drivers must either produce proof that they were not at fault, or they are presumed to be at fault. And because of this burden of proof, Dutch motorists drive carefully.

In the case of the truck driver who hit Hananja Konijn, he was charged within days of the collision, and a year later, was handed the maximum sentence of 240 hours of community service, a suspended sentence of 2 months in prison, and the loss of his driver’s license for 18 months.

Within a month of the fatal collision, the intersection where young Hananja lost his life was redesigned. A mirror was installed beneath the traffic light to help drivers see approaching cyclists, a bike box was installed, so that cyclists would be able to cross the intersection before a driver could right-hook them, and the bike lane was doubled in width by removing an automobile lane, and painted bright red.

As one Zoetermeer resident explained, “When you have an incident with such an impact on the community, with such feelings of anger, you have to show the people you’re taking it very seriously. You actually have to change the situation to make it less dangerous.”

Hananja Konijn’s roadside memorial

The contrast with how we respond to cyclist fatalities in America couldn’t be more stark.

And the results are predictable.

In America, each willful failure to protect cyclists ripples out, affecting untold numbers of other people who decide that cycling is too dangerous to risk. The number of children who are interested in riding a bike is plummeting. We’re raising a generation of people who will have no youthful connection to riding a bike when they are adults. These are the people who will be driving within a few years, and we’re training them to both fear cycling as “dangerous”—ironically, because drivers are dangerous—and to also have absolutely no personal experience of or connection to cycling.

In response to the blatant societal-wide disdain for cyclists, and utter lack of regard for their legal rights, their safety, and their lives, increasing numbers of cyclists are removing themselves from the roads altogether. In Britain, where conditions are no better than in the United States, increasing numbers of cyclists are also removing themselves from the roads, preferring the safety of indoor cycling to the risk of cycling on the roads we built.

In America, the conditions we create on our roads favor the strong and fearless cyclists and the risk-takers, but discourage almost everybody else. This is the negative ripple effect that comes with each cycling death, with each near-miss, with each willful failure to protect cyclists and to shift the blame to the victims of careless driving.

But it doesn’t have to be that way.

There’s a different kind of ripple effect—the kind of positive ripple that comes when people see that their safety is taken seriously, and that cycling is safe, not just for the strong and fearless, but for “everybody from 8 to 80.” We know this positive ripple exists, because we can see the results where people know that their safety is a societal priority, in the Netherlands, and in Denmark. The sheer numbers of people—everyday, ordinary people who may not even think of themselves as “cyclists”— riding in these countries demonstrate that when people feel that their safety is taken seriously, they will ride. It’s not necessary to be a strong and fearless rider, or a risk-taker, or specially-trained, or to wear helmets and lights and fluorescent colors. It’s just necessary to prioritize cyclist safety, to stop shifting the blame for collisions from careless drivers to their victims, and to stop normalizing and excusing dangerous driving.

When we do these things, people feel safe, and they will ride, because they know they will come home safe at the end of the day. This is the positive ripple effect. And when we don’t do these things, when we exonerate dangerous drivers and shift the blame to their victims, when we respond to each cycling fatality with ticket blitzes against cyclists, while turning a blind eye to dangerous drivers, when we malign cyclists as “scofflaws” while ignoring the scofflaw drivers, when assaults against cyclists are “funny,” when only the strong and fearless cyclists, and the risk-takers, and the specially-trained cyclists feel “safe,” in conditions that make everybody else feel unsafe, we create a negative ripple effect. We can see that too, in the already low and dropping numbers of people who ride, and the growing numbers of people who think “nope, too dangerous for me.”

We have a choice. There’s a better way, if we want it. But it’s up to us to make it happen.